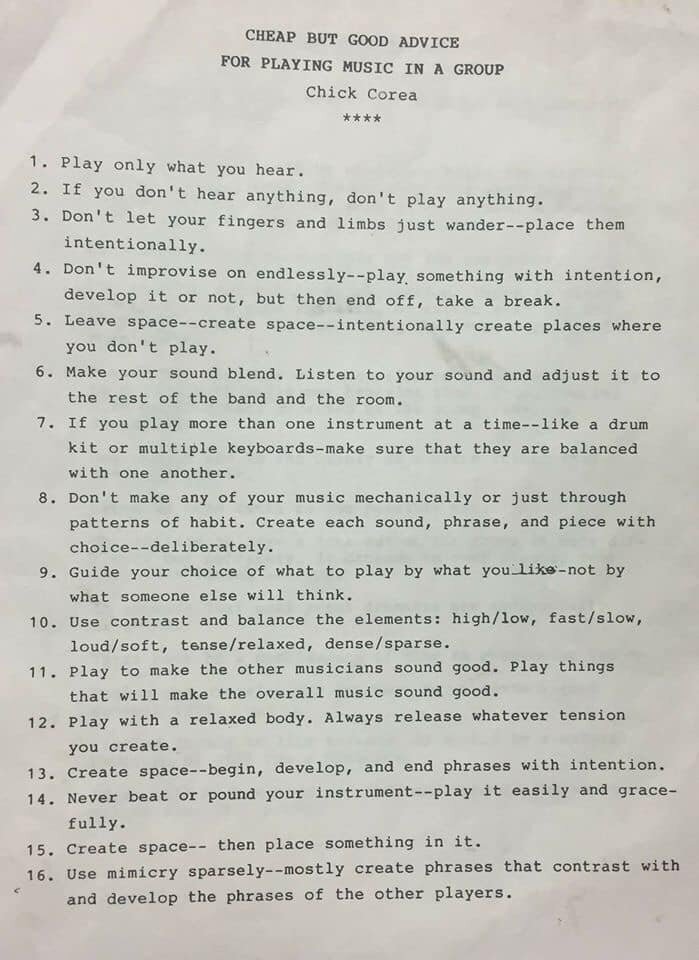

Performance Advice from Chick Corea

Sixteen rules for playing music in a group, written by Chick Corea.

Read MoreSESSION | PERFORMANCE | INSTRUCTION

Lucas Ventura - professional session drummer and drum instructor. Drum lessons in the Boise Idaho region.

Sixteen rules for playing music in a group, written by Chick Corea.

Read MoreHaving a perfectionist mentality is a double-edged sword. As a teacher, I always appreciate the student that hungers to perfect the craft. In a sense, there's nothing I desire more in a student than the drive to master their studies! Yet it fascinates me that the same impulses that drive us to get a thing just perfect often come with some reactive qualities that detract from efficiently learning.

One of the techniques I teach my students in mastering a passage through repetition is continuous playthrough. This means to continue playing without stopping the groove, short of mistakes that cause us to completely lose our place in the music. The perfectionist in us though, wants to stop at every error and restart at the beginning, or some relative point. I have found over the years that in most instances though, this approach hinders us. The primary aphorism I use to express this is that, "if you were playing a concert and made a mistake, would you stop the band and the whole song and start over?" The answer, generally speaking, is "no!" The show must go on, as the colloquialism goes. So, with the best of intentions to get a part right, what we are actually doing is training ourselves to stop at every mistake. Thus mentally, we freeze at the realization of an error. This can have disastrous consequences for a performer.

Therefore, it is necessary to train ourselves in a way where the perfectionist goes away for lunch, and comes back when we have things mostly in order. We play through a passage, get a part of it wrong perhaps, but focus on playing as much of it correctly and in time as we can, recognizing but being only softly critical of the troublesome section. Once we have the general concept acquired, then we gradually increase the intensity of our efforts to play the tricky stuff. The point that we let the perfectionist back in the room is when we have cleanly isolated the spot giving us trouble and we can freely fuck it up without utterly derailing ourselves from playing through it.

In other words, don't be afraid to screw up a tricky fill or complex beat. Just learn to do it without losing your time. If you stop yourself every time you make a mistake, you will choke yourself off from things such as the spirit of improvisation, which is the part of us that sometimes ventures into the expression of experimental musical ideas- things that maybe we'll pull off, maybe we won't. But half the fun of going for it can be the excitement of uncertainty that comes along with it. If you are obsessed with perfection, it will be hard to allow yourself to venture into the unknown, which restricts you from an entire landscape of musical exploration. Again, the key is to will yourself to play through uncertainty and unperfected passages with attention to time. Get back to the "one" and you're probably safe. Then you get to approach it all over again, without having to restart your momentum. This leads to more continuous repetitions of the problematic phrase, giving us a chance to efficiently attack it until we wear down the physical puzzle before us.

Another concern I have with perfectionism is the tendency to overly focus on technical aspects of our playing over feel and style. You can be a technically superior drummer who can diddle and flam your way all over the drum kit while being right on every beat of the metronome, but if you don't let loose, explore the unknown, or stick your neck out once and awhile, there's a good chance you'll sound really square, too. Now, there's a place for that, and there's no right or wrong to things like this. But if I had my druthers I'd go see The Ramones at CBGB's over any RUSH concert ever, is all I'm sayin'.

On the other side of the consideration, I don't encourage sloppiness and carelessness. What I appreciate about the perfectionist is the sharp attention to detail that is being constantly sought out. Indeed, "It's good enough for rock n' roll" is a phrase I've heard indefensibly uttered way too many times as a lazy excuse for unprofessionalism or some hubristic assumption that sloppiness itself translates into style. Sure, there are sloppy musicians that captured a sound and a style and it's amazing when that happens. But it's only a correlation for the most part. Maybe it's part of a mentality, but one that evolved naturally for those magical musical moments and groups in history. Mostly what I see from musicians that actively embrace that kind of attitude or mentality is that they are just way more into their pants and hair than their music.

The key is to keep perfectionism in the right view. We often must relax it for the sake of getting a general feel for a new musical idea- let ourselves be sloppy and gradually mash the thing together until it has some relatively coherent shape to it, and then progressively turn up the dial on perfecting a thing until it sounds and feels exactly like it's meant to.

Two things I love. Drums and juggling. Now, although I meant to discuss how one relates to the other, I felt like I had to mention an old inspiration of mine who happens to do both at the same time.

Years ago, living in Phoenix AZ, I used to go to this jazz/blues hangout spot called Char's, and every so often this blues band from Tucson called the Bad News Blues Band would come in and rock the house. Now, I don't think he plays with them at this point, but at the time (this was maybe fifteen years ago) the drummer was this guy Chip Ritter. Chip is a really cool guy. Very exuberant personality, great performer, great hands, and on top of all that, he had this trick under his belt- he could juggle three sticks and play! It was always a trip to see him bust that out. In fact, a few years down the road from that time he managed to show it off on the Late Show:

Anyway, I felt like I had to throw that in, because seriously, how can you talk about juggling and drumming and not mention Chip Ritter? But I'll leave the advanced stick tricks to Mr. Ritter and discuss my initial thoughts that motivated the blog.

Last week I was teaching a younger student of mine who is working through a very common challenge musicians face, which is keeping attention on peripheral facets of playing while directly focusing on one particular aspect. Specifically this student was focusing on correctly playing what he's reading while keeping time and maintaining proper technique. This student in particular finds it more challenging to keep track of maintaining one without a significant sacrifice to the other two. We tried out a little 'attention exercise' where, through the repetition of a single phrase we bounced our attention from each object to the other at some different intervals. It was a good introspection for him to see how bouncing his object of focus changed the way things were being played. At the end of the lesson, I handed him a set of juggling balls and told him to start learning to juggle. I'm probably just being eccentric, but that was my intuitive decision about how to help him move forward outside of the practice routine.

Musicians must develop a strong 'peripheral view' of the multiple elements we have to keep track of. Time is especially important for drummers since if we lose time, every other musician in a group would be forced to shift tempo along with us. Yet, it's relatively easy to lose track of when you are singularly focused on some other aspect of playing. Technique is similar for a beginner until they develop it to a point of clockwork automation. And naturally, the material we are playing tends to take up the majority of our focus most of the time. So in this way, I imagine those three objects to be like three juggling pins being thrown hand to hand.

If you have any experience with juggling, then you will know that in general it's useful to avoid any singular focus of your attention. There may be a trick that involves an increased attention to one of the objects, but to lose sight of any other object increases the likelihood that we miss a catch or throw something wildly. In other words, the juggling is the object of focus. The greater coordinated act itself becomes a thing. I think this is a perfect analogy for what has to be done by a drummer when we are playing, or for performance in general.

On stage, I feel that I rarely am thinking about technique, but there are other elements that come into focus. Of course, there is the material at hand. There is time. There is the listening and watching of the other musicians- looking for improvisational cues, mistakes I might have to follow, or just general dynamics to make sure I'm not playing too loud in a small room. There can even be attention on how I'm performing. All these things have to happen simultaneously and consistently. If I focus too much on what I'm playing, maybe my time suffers and I drift. If I'm too externally focused on another player or something happening on stage, maybe I miss a change or hit. If I'm digging too deep into the feel of the music, then maybe I close my eyes and get all trancy vibed-out and completely miss the singer signaling me to cut the next musical section because he just broke a string. It could be nearly anything.

The last aspect I think I'd like to touch on here is how important it is to have that wide peripheral attention, but also a relaxed clarity and focus. You could perhaps refer to it as mindfulness. There are so many potential distractions that a performer can face. Some of the worst ones are purely psychologically manufactured (ie. stage anxiety), but most of the time though it's something like an equipment malfunction, audio feedback or a bad monitor mix, a crowd distraction, or even the distraction of getting stuck on the mistake I just made. It's a mark of skill when one can continue on unabated in the face of technical difficulties, or handle a show-stopping problem with grace. In a way, I think perhaps the pinnacle of being able to juggle the various aspects of performing is the ability to remain focused in the face of severe distraction. One of the raddest things I love is when I see a performer smash straight through some chaos on stage without losing their performance mindset.